I recently had a chance to see the 4K restoration of this movie, and to see Julianne Moore and Todd Haynes “introduce” the movie. They were fine but mostly just said how much they enjoyed working together and how it came to be that this was their first movie together. It wasn’t a Q&A, which I gathered they had just done for the previous showing. Poor things were tired.

I would have loved to hear what they — especially Todd — had to say about it. It’s a completely indescribable movie: ambiguous but in absolutely all the right ways.

One thing he said that kind of gave me a clue as to what he was intending, was that his producing partner (I think he meant Christine Vachon) had said to him, after the umpteenth rejection, “Are you sure you want to make this movie?” And he told us, the audience, that he said he really wanted to make a movie about this woman.

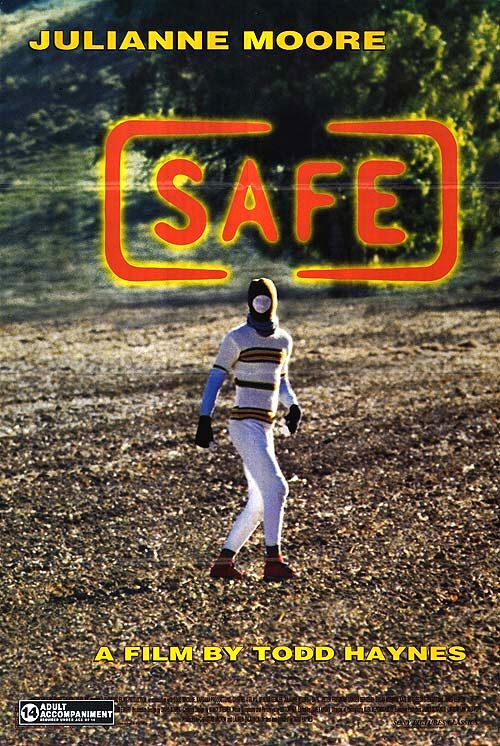

I think moving the emphasis from the idea of environmentalism or illness to this particular woman’s journey is helpful. Because when I saw it in the 90s I could not stop interpreting it through the lens of HIV/AIDS and what I had just lived through, which included a number of deaths of friends and acquaintances between 1983 and and 1995, when this movie was released. (It took place in 1987 and was filmed in 1992.) The title was also a kind of punch in the face, as “safe” at the time, conjured up thoughts of sex, condoms, etc. And it’s also vaguely sci-fi — especially with the poster above.

I remember some people seeing it specifically through the lens of environmentalism, modernism, etc., and I, myself, could not help seeing it through an additional lens of religious fundamentalism, because the community where she ends up brought back personal nightmares of being trapped in that religious environment where you were supposed to enjoy happy songs and songs about Jesus.

Now, decades later, the movie feels like it’s about anti-Vaxxers, gluten intolerance, lactose intolerance, autism, and even, to a lesser extent, about transgenderism. I think the reason our interpretation can change over time is because he managed to capture something that is both eternal and also rooted in a particular culture. There is a medical term or medical conundrum, which I can’t remember, but it’s basically that every age has a “made up” condition that seems to afflict huge numbers of people. But there is no actual condition — it’s just a large cultural delusion. So in one age, the one depicted in this movie, it’s “environmental toxins,” while in another age, it’s “chronic fatigue,” and then there are conditions that go back to issues like “melancholy,” and excessive bad blood. There was a time when people who felt sick and tired only began to feel somewhat better if they had their blood drained with leeches. There was a time when people insisted that their doctors had to taste their urine.

Now we have people carrying on about vaccines causing autism, and 5G signals causing Covid or, more properly, the novel coronavirus by “thickening” the blood. One of my own relations believes that his daughter, who is transgender and was known as male until she “came out,” thinks that it was “caused” by an excessive hormone secreted by the mother during the pregnancy and specifically acted upon by microwave radiation.

So the movie addresses, in some sense, all of these made up illnesses and conditions, but it very adroitly and importantly combines them with actual diseases. The main leader of the quasi-religious group where she ends up has AIDS/HIV which is a real disease, caused by a real virus, and was killing people for decades — since at least the late 40s. It exploded in 1980 when a San Francisco doctor realized there was an outbreak of something unknown happening to his patients. That focus — that concentration of illness — actually allowed us to progress and learn more about it, but until then, there were people who died of something without any explanation at all.

And that’s what the film captures so perfectly. That there are many reasons why someone might be sick and why it might be real. But the invisible nature of these things that stalk us mean that we will probably end up looking like a crazy person when we keep insisting that we’re sick and trying to come up with reasons why.

But there is also another thing going on in the movie, which is the inability to examine oneself. Disease in this movie is a crutch — a way of avoiding self examination. That comes through in the many instances of the vapidity of the main characters life before she develops her chronic condition: like at one point when a large couch is delivered that is the wrong color, they tell her that the original order is for the brown or black couch. Her answer is that that isn’t possible, because that color wouldn’t go with any of the other furniture. Later, when the leader of the group is trying to explain away having AIDS, he blames the modern world and everything else for creating blood toxicity. These people cannot face themselves. And the word and title “Safe” means, essentially, safe from oneself.