David Cronenberg invented, apparently, the body horror genre, but I think the word horror is really a terrible description of his fascination. The last movie he made, people were watching surgeries as entertainment. These surgeries would take place without general anesthesia, upon people who had grown strange, unique and apparently superfluous organs. The removal of these organs is what people found exciting and in the case of the hero, his organs had been tattooed while inside his body, so each removal was also a piece of artwork.

But ultimately, what was really going on, and it seems like a subplot for the longest time, is a different group of people who could not eat regular food. If I’m remembering the plot right — does it matter — we didn’t find out until the end that all these superfluous organs and people who couldn’t eat food was because they were evolving to eat and digest plastic. The “horror” of this body focused story is environment disaster, not one’s revulsion to the body.

And I think if you look at most David Cronenberg movies (and perhaps David Lynch as I almost mistyped), there was always “something else” going on that affected humanity in a profound way. Videodrome wasn’t really about James Woods developing a vagina in the middle of his abdomen, into which people would place videotapes and later, a gun. It was about the persistence and overwhelming presence of television in our lives and, a hint in the manner of Olivier Assayas’s Demonlover, that pornography was invading every aspect of life.

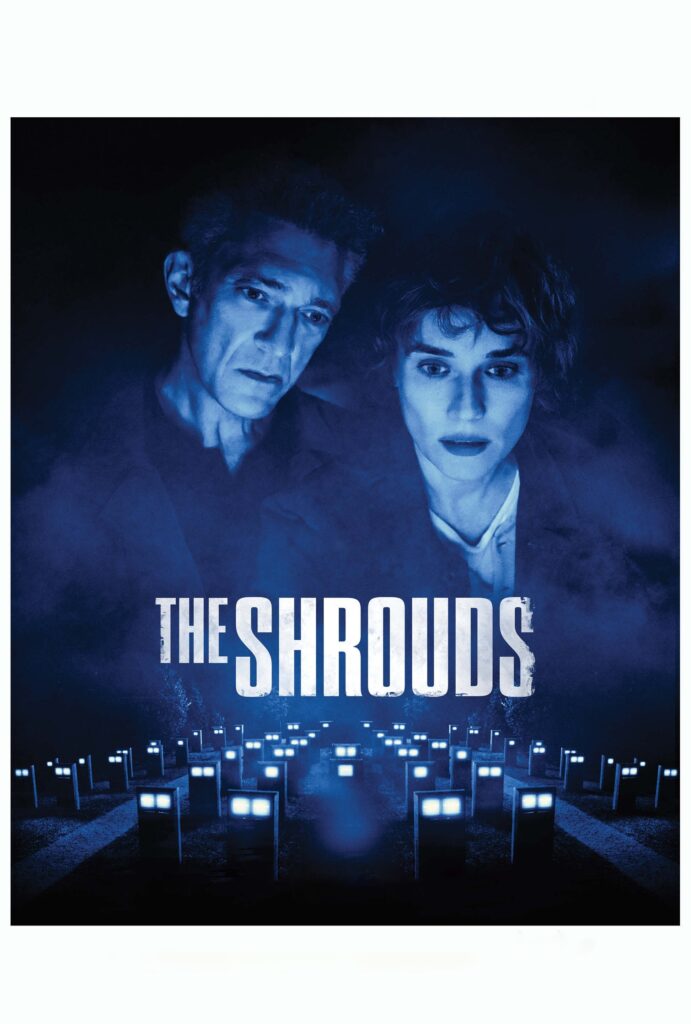

The Shrouds could be a warning about technology and, I would add, its corruptibility. Corruption is an interesting word to use here because one of its definitions is decay, putrid, etc. — like the corruption of the body as it decays in a grave. In this movie, a few dead people, including the main characters wife, are wrapped in shrouds — shaped like the cocoon a spider might make — and this allows through wires and screens for people to watch their loved ones’ bodies decay. Some people are comforted by this. Some of the graves are vandalized but it turns out that it is not an accident and then corporate conspiracies and such take over. Not sure how much I cared, but I am sure that most of us do not see what is actually going on in a movie because we are too focused on the plot and can’t weed out the parts from the whole. David Lynch’s Eraserhead, at some level, can be seen as a plea for sympathy.