I’m not sure if they actually released a movie poster for this film, but this seems to be at least a poster for the movie when it played at Cannes.

I’m not a Martin Amis fan so I have not read the book, but apparently Jonathan Glazer radically re-adapted this novel to fit his vision of what evil looks like. There are also a few flaws with his adaptation and one is that you have to understand something about Auschwitz in order to understand the movie.

Without an understanding of what the “ovens” meant, or “ash,” or random gunfire, trains heading toward a walled camp, and the barbed wire on those same walls, you’d probably not understand a thing about this movie.

I was pretty certain, and I was right, that horrible reviewers like Manhola Dargis would bring up the “banality of evil,” phrase that Hannah Arendt coined, but I don’t think this movie is about the banality of evil, but much more about how ordinary and perhaps — even more important — untalented people can blind themselves to the horrors that they are inflicting on, in this case, about 3,000,000 prisoners. And yet, are they blind? Or is there some moral flaw in the human mind that rationalizes the wrongs being committed in order to keep living in paradise. (The mother of this clan — Hedwig Höss — referes to their home as a paradise.)

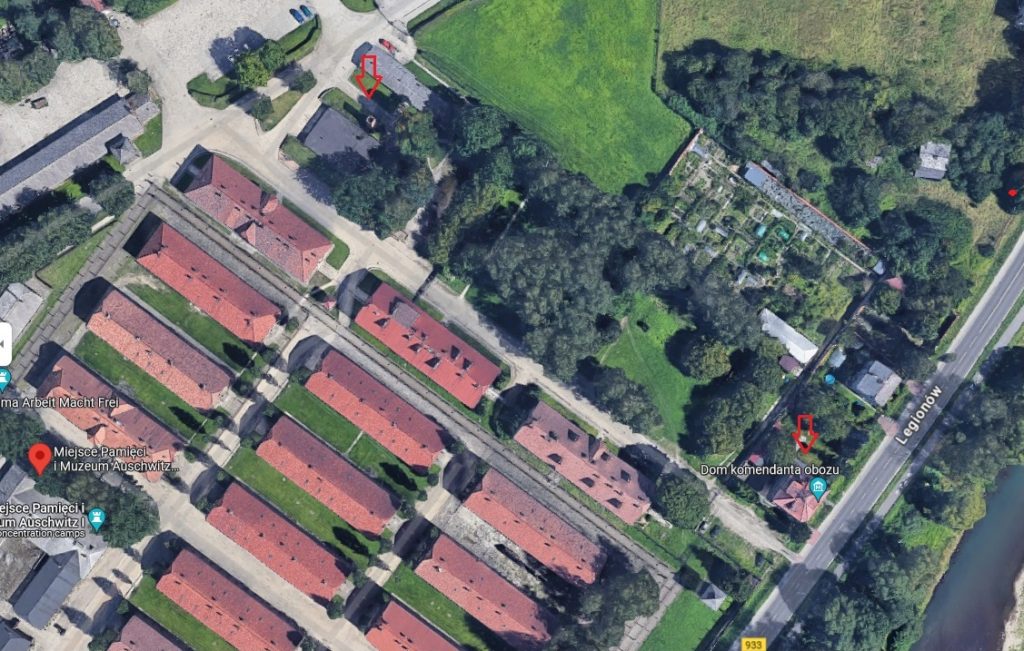

Just to go back and do a plot summary, this movie is about Rudolph Höss, who was the commandant of Auschwitz death camp for about four years. He and his family lived in the southeast corner of the original Auschwitz prisoner camp and they apparently lived a very luxurious life, with a large garden, a small swimming pool, a backyard gazebo, and a lot of slave labor to help them maintain it. The movie focuses solely on these people and their children. It never once shows us what’s going on inside those walls. Other than the slave labor, it doesn’t show anything except how this family ignores — but that’s not the right word — embraces maybe — the killing that’s happening on the other side of the barbed wire.

A small detail early on is when a prisoner pushing a wheelbarrow, comes through the camp to the back door of the commandant’s residence and drops off two sacks. They contain clothing, and one contains a full length fur. Hedwig allows her laborers to take whatever they want from one sack, but takes the sack containing the fur to her room and shuts the door. She tries it on to see how glamorous she looks and that single act, suggests she knows absolutely what’s going on and what she is participating in. A little later you hear some Polish or German women laughing about one of the slave laborer’s taking a tiny little Jewess’s dress and not fitting into it.

Auschwitz 1 is still there. It was originally a prisoner for Russian p.o.w.’s, but eventually, under Höss ‘s command, it became a death camp. The home is in the lower right in this google map photo. It’s labelled Don Komendanta obozu, which I think means The Commandants abode. In the movie, the garden and pool extended up NNW in that clear space which looks like a small field. Toward the top of the photo with the red arrow is the first crematorium. In the movie, this chimney is seen constantly smoking or burning orange and red.

When the Germans expanded their extermination campaign, other camps were built in the area — they have different names like Auschwitz-Birkenau, etc., and were march larger.

There are a multitude of reactions in this family to what’s going on in that camp. One girl has become a sleepwalker, and using a thermal camera the director captures her sleepwalking dreams which mainly consist of her gathering apples and leaving them in places for, presumably, the prisoners. A boy can’t stop staring at the flames coming from the chimney because he’s troubled by them. Most effective, however, is Hedwig’s mother, who has come to stay with them for an unspecified time, but it seems like it’s supposed to be a permanent move. She is horrified by the smoke (and when the wind changes direction the smell comes into the house in paradise and all the windows have to be shut) and without saying a word to her daughter or anyone else, she packs up and leaves. And Rudolph, when he is at some big gala in some town that is quite far from their home, calls his wife and tells her that he mostly spent the night thinking about how he would gas this crowd and explains that the ceilings are too high there.

Höss’s testimony at Nuremberg was creepy and horrifying. (The movie ends long before he is caught and tried.) Basically he admits that he killed and burned between 1.5 and 3 million people, but that he didn’t really keep the numbers. And basically, the psychology behind what happened there and elsewhere has occupied minds (like Sigmund’s daughter Anna Freud) and others for the last 75 years and is ongoing, as we can see with so many Trump/Maga people who are calling for the extermination of liberals and leftists and with Trump himself starting to use Hitler style language such as “infecting our blood,” and “vermin.”

But for me, that fur coat scene tells you nearly everything you need to know about how we blind ourselves to the evil we do. As long as the gifts keep coming, we can reduce people to others, and then never have to look at them again. And I for one, think this adaptation perfectly encapsulated how we commit evil by not seeing it.

Höss, like all cowards, tried to hide as a gardener. But he was found by a Nazi hunter, tried and was hanged. At the request of survivors he was executed at Auschwitz. He was the last execution in Poland. He wrote some interesting letters to his family after (after!) he knew he was going to be executed. He wrote that he had blindly believed in what his superiors said and their philosophy, and he told his son never to believe without questioning. (I’m paraphrasing of course.) But I have to take that contrition with a grain of salt, because he had basically been a career criminal before he ended up joining the SS. He was always on that path and probably always had murder in his heart.